A selection of what our editors have been reading and recommending this summer:

Adam Z. Levy, Publisher

Marie Ndiaye is one of those rare writers who finds herself brilliantly at home in the uncanny. In Ndiaye’s most recently translated novel, My Heart Hemmed In (tr. Jordan Stump), which comes out this month from Two Lines Press, two schoolteachers, Nadia and her husband, Ange, find themselves objects of sudden disgust, mysteriously cast out by their community. Ndiaye has learned a thing or two from Kafka about the shape of a world bound by an indescribable menace, but this book is distinctly her own. Hands down one of my favorites of the year.

There’s a lot to love about Gabe Habash’s debut, Stephen Florida (Coffee House Press, June 2017), which centers on a college wrestler in North Dakota, who’s got his eye on winning the Division Four national championship. Maybe it’s the obsessive circling of Florida’s mind or the way the language of the ring finds its own music that’s got me recommending this book left and right this summer. In Stephen Florida, Habash has written one of the most delightful portraits of a mind on the verge of coming undone.

Ashley Nelson Levy, Publisher

I picked up Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon (NYRB Classics, April 2017, tr. Jenny McPhee) on the recommendation of one of our authors, Andrés Barba, who also translates from Italian to Spanish. “You will love her,” he said, matter of factly. He said this without knowing that my mother’s side of the family is large and Italian, and that I’m drawn to books that might sound like my childhood.

Family Lexicon sounds nothing like my childhood, though, with Mussolini’s Italy in the background and a father who divides the world into jackasses and nitwits. But Ginzburg has hit on a beautiful truth: the collective language of family always binds, no matter how large or how loving or how unhappy the crowd at the dinner table. You can still count on the bad jokes and off-color remarks to bloom one day into nostalgia. With sentences built effortlessly from Ginzburg’s wit, melancholy, and sharp observation—hats off to translator Jenny McPhee—we see a family held together by its stories.

Liza St. James, Editorial Assistant

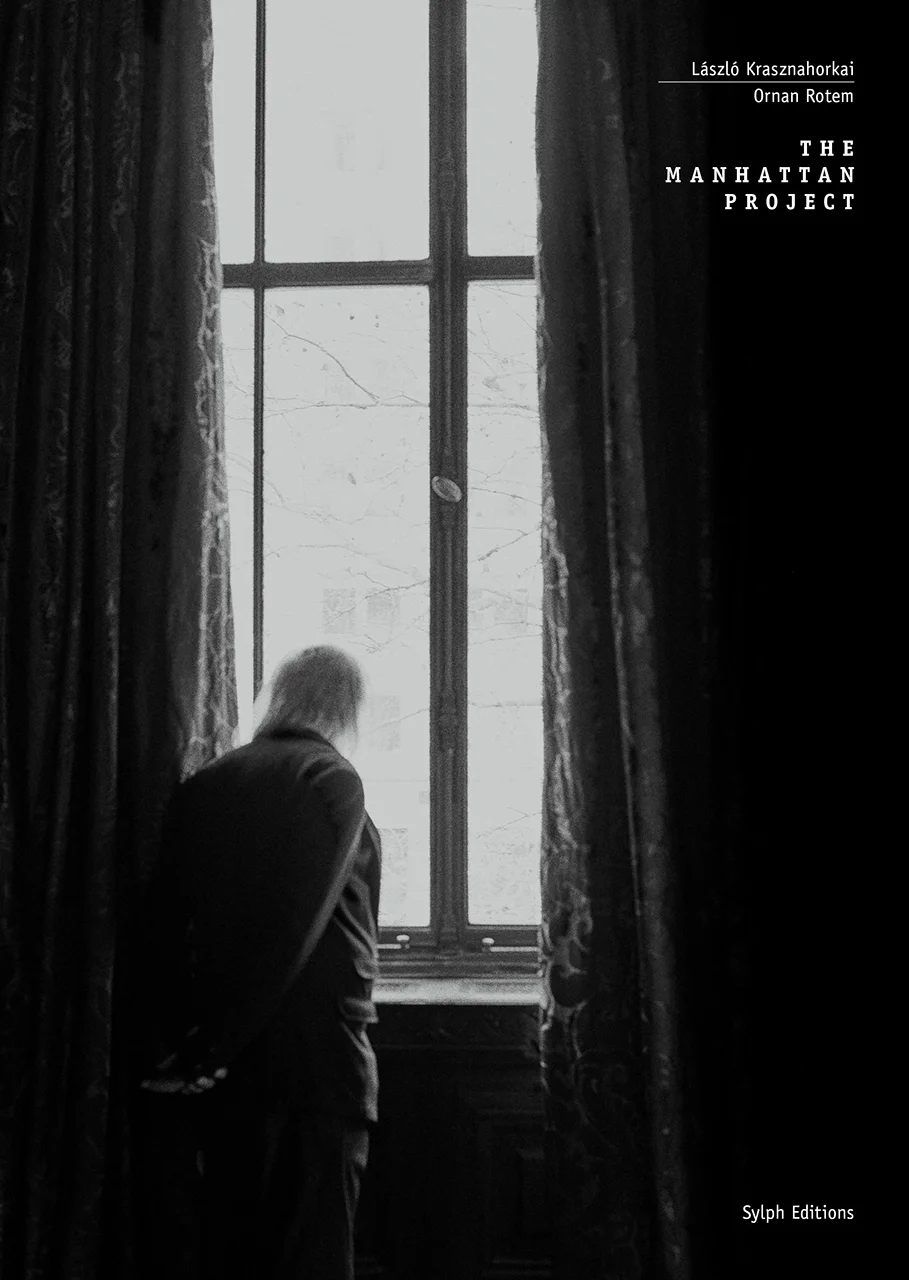

The Manhattan Project (Sylph Editions, June 2017, tr. John Batki) is László Krasznahorkai’s diary of chance encounters while following the traces of Melville’s Manhattan years—and the literary and fictional followers of those same traces before him—complemented by Ornan Rotem’s stunning black and white photographic essay. It gave me that phenomenal feeling of being on the heels of something, in the presence of a force. It’s a feeling I’ve experienced myself—one that I’ve moved to various cities and across seas in order to obey. I always appreciate when I get it second-hand, too; it’s not unlike the hauntings I felt reading Suite for Barbara Loden, or that I nearly always feel reading Susan Howe. Here it’s fastened to Manhattan, and replete with multi-page foldouts, compelling ghost-moved readers to get in on it all. As a Melville-worshiper myself, this book struck a particular chord with me, but I imagine it will entice anyone who’s ever retraced another’s footsteps and had a thought along the lines of, as Krasznahorkai repeats, “Only Melville interested me. Only Melville, although I did not know why.”

I felt a similar affinity for poet Arisa White’s Electric Literature article, “Walking the East Bay in the Footsteps of Maya Angelou, June Jordan & Pat Parker.” In it, White describes her journeys to various addresses found among old paperwork at the Poetry Center and American Poetry Archives—the chance encounters they brought about, the new work they introduced her to. She writes, “I’m having a rooted experience of their poetry — it belongs to space and time, to people, to a constellation of exchanges and encounters that rooted them to this world.” And it’s been a treat, for me, to accompany these writers on their embodied investigations—and to plot some of my own.

Paola Vergara, Editorial Intern

Robert Hass’s A Little Book on Form (Ecco, April 2017) is a casual but thorough journey into the history of poetic form. Starting from the most basic building block, a single line, Haas leads the reader, gently and tenderly, through the structures of the haiku, the sonnet, the blues, the ode, and the elegy only to discover that we are not only unraveling the foundation of language but also experiencing the development of human thought, using such examples as Ginsberg, Milosz, Catallus, Hughes, and Bashō. For a reader like myself, who is enamored by the structure and order of language, this careful dissection of poetry by the ever amiable Hass is an illuminating read.