Postcard from Planet Omicron

MARY CAPPELLO

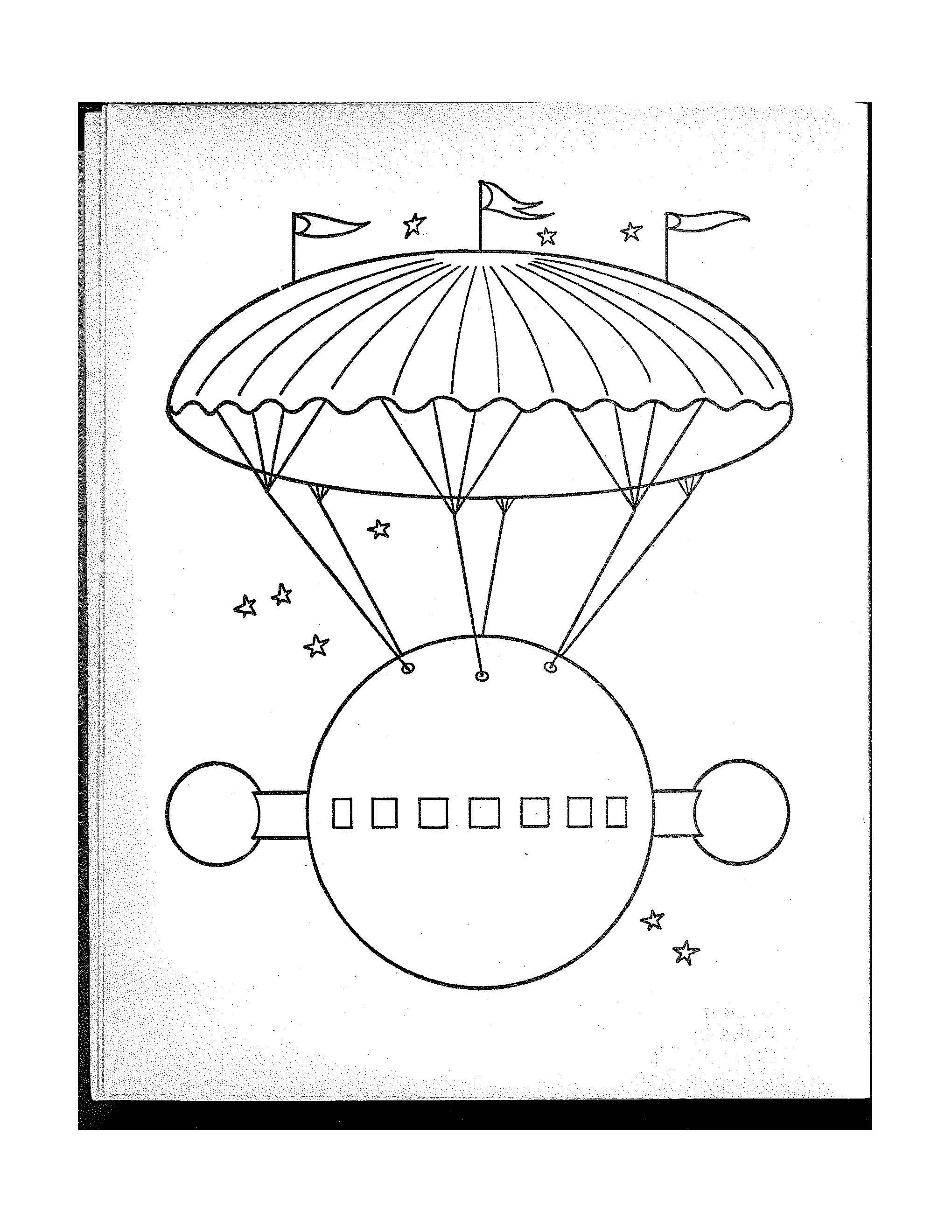

“Captain, come quick! I’m picking up something unusual. It looks like a floating circus tent.”

I am writing from a place of the synchronous and the overlapping, from the lost-to-time and the prescient. I am writing from the vantage of a Star Trek coloring book, circa 1965, that narrates the crew’s encounter with a mysterious (lost) planet, “Omicron.”

I found the book in a store in Providence, RI, called Rocket to Mars, where I’d sought the perfect holiday gift for a young artist friend, Caeli, who, though not of the Star Trek generation, had a penchant for old-time TV shows, the campier, the better. It was buried beneath a stack of 1960s ephemera, and I chose it simply for its cover—a fetching portrait-in-oils of Spock; when I got home and discovered the pure serendipity of its contents, I felt for a moment that I might not be able to part with it. Then it was hard not to read the book as a gift from the universe, a message in a bottle, a gloss on our own current circumstance.

Spock reads out from a large Atlas-shaped folio called Space. No one has made contact with Omicron in a century, he reports. The planet is inhabited solely by circus performers. Omicron’s clowns, discoverers of “the secret of happiness,” humbly bow to their visitors from the USS Enterprise, each of whom is required to don circus attire. This makes them suddenly happy and unable to resist the impulse to tumble or stand on their heads.

There’s a leavening bounce to everything on planet Omicron, its dominant shape, an orb, from the soft and rubbery spheres that crown Omicronians’ elfin shoes, to the buttons that fasten their tunics, the balls that pinch their noses, or the globes that transform stately turrets into party hats.

As COVID-19 variants go, Omicron is special. It has more mutations than any other variant, and it is possibly reversing the logic by which viruses are understood to evolve. Digitized renderings present the virus as a luridly metallic popcorn ball, bursting at its fluorescently oozing seams.

Star Trek instructs differently. Heir to its own strange gravity, Omicron is held aloft by a parachute and topped with flags that know no territory. It’s a figure for the imagination, abundantly available, and relative of joy.

Let me come back to Caeli because she’s the person who brought me here.

When Caeli was 12, we called our meetings “homepleasure” in lieu of “homeschool”; my lesson plans are still extant, so old as to be vintage:

Invent occasions that call for confetti.

Record a personal lexicon: Cae: ultra-ly; flippety gibbetty; confusled; Me: gee willikers; kerfluie.

Does puzzle have an opposite? If not, why not? Are you a puzzle? In what sense?

Seek out joy, as incident and event. Today, magenta; tomorrow, aquamarine.

Omicron seems to have discovered us, not vice-versa. We need to feel its contours not as code, but wax applied to paper, to discern the shape by which it seeks to color us in.

Mary Cappello’s seven books of literary nonfiction include a detour on awkwardness; a breast-cancer anti-chronicle; a lyric biography; and the mood fantasia, Life Breaks In. A former Guggenheim and Berlin Prize Fellow, she is a professor of English and creative writing at the University of Rhode Island. She lives in Providence, Rhode Island, and Lucerne-in-Maine, Maine. Lecture, her speculative manifesto on the lost arts of the lecture, the notebook, and the nap inaugurated Transit Books’s Undelivered Lecture Series.