Postcard from Paris

JOANNA WALSH

I’m in Paris. I’ve been coming to Paris all my life. But wait, let me tell you what I mean. It’s not what you think: I was in my mid-20s when I did more than pass through one of its stations, and in my mid-30s by the time coming here became non-negotiable.

What I mean is I’ve always wanted to leave. What I mean is I’ve always needed a reason, not only to leave where I was (if you get where I’m coming from) but an idea to travel towards.

What I mean is I was always dissatisfied. Dissatisfied with family, with home. As a child how I longed to be old enough to just go though, then, I had no idea where; as an adult, the same, which makes me wonder why I ever consented to reproduce a situation in which, I had good evidence, I was likely to feel an imposter.

Coming to Paris this time, years later, I made myself sick getting here. I took on too much and tried to finish each task as completely as though I were leaving not a place but my life. The week before I left: three countries, six cities, three speaking events; deadlines; family shit which I try so hard to do right though can’t overwrite the things I’ve done wrong. Arriving at the residency, I lug a 20kg suitcase up and down metro steps. What am I trying to do to myself?

The first night, the second night at the residency I wake in panic: insomniac, sick, exhausted, why had I wanted to come here? The floor of the single room is cold hard lino; several of the wooden struts supporting the mattress are broken; the wardrobe is tiny and there aren’t enough coat hangers; in the kitchen, the pans have no lids; there is no plug in the sink; there are no towels. How can I stay? Right now it will be exhausting to remedy these problems. And expensive (don’t imagine I’m in a position to wave a financial magic wand with a light heart). For the first time in Paris I want to leave Paris. But where could I go? Unanchored, I don’t know. Somewhere that feels like home, the place where I’d always felt out of place; the place I’d thought I was so bad at, so bad in; the place I had rented out so I could afford to come here; the place to which I can’t (for the moment) return.

No ideas but in things, wrote William Carlos Williams. And Paris is built of material ideas, ideas to travel towards.

I found a piece of metal pipe in a store cupboard and improvised a hanging rail between the tiny wardrobe and the bookcase. I tested it and my clothes weighed it down so it stayed in place. I found cut-price towels and coat hangers on sale in Monoprix and, signing up for their loyalty card, was rewarded with an extra discount. I bought the strongest non-prescription sleeping pills in the pharmacy. I found a new pair of jeans in my size in the street: ‘please take’. I discovered two rolls of corrugated cardboard left by a former artist resident, and made them into a sort of screen to divide my space that undulated (I fancied) like a piece of domestic furniture made by Eileen Grey, the early 20th century Irish designer I’d had in mind since that afternoon’s zoom meeting with the artist who’d made that great video piece about Grey in lockdown.*

I bought a Marseille soap and it smelled like nostalgia for no home I’d grown up in; a nostalgia I could travel towards.

That night, a friend** invited me to his show, a performance lecture on proxies, on the preposterous imposterhood of sending someone in your place to speak your words; on what happens to the reader, the writer, the audience when they enter into a contract tied by this performance. My friend, the writer and director of the piece, was there this time to watch, though its initial iteration had been designed precisely to accommodate his absence.

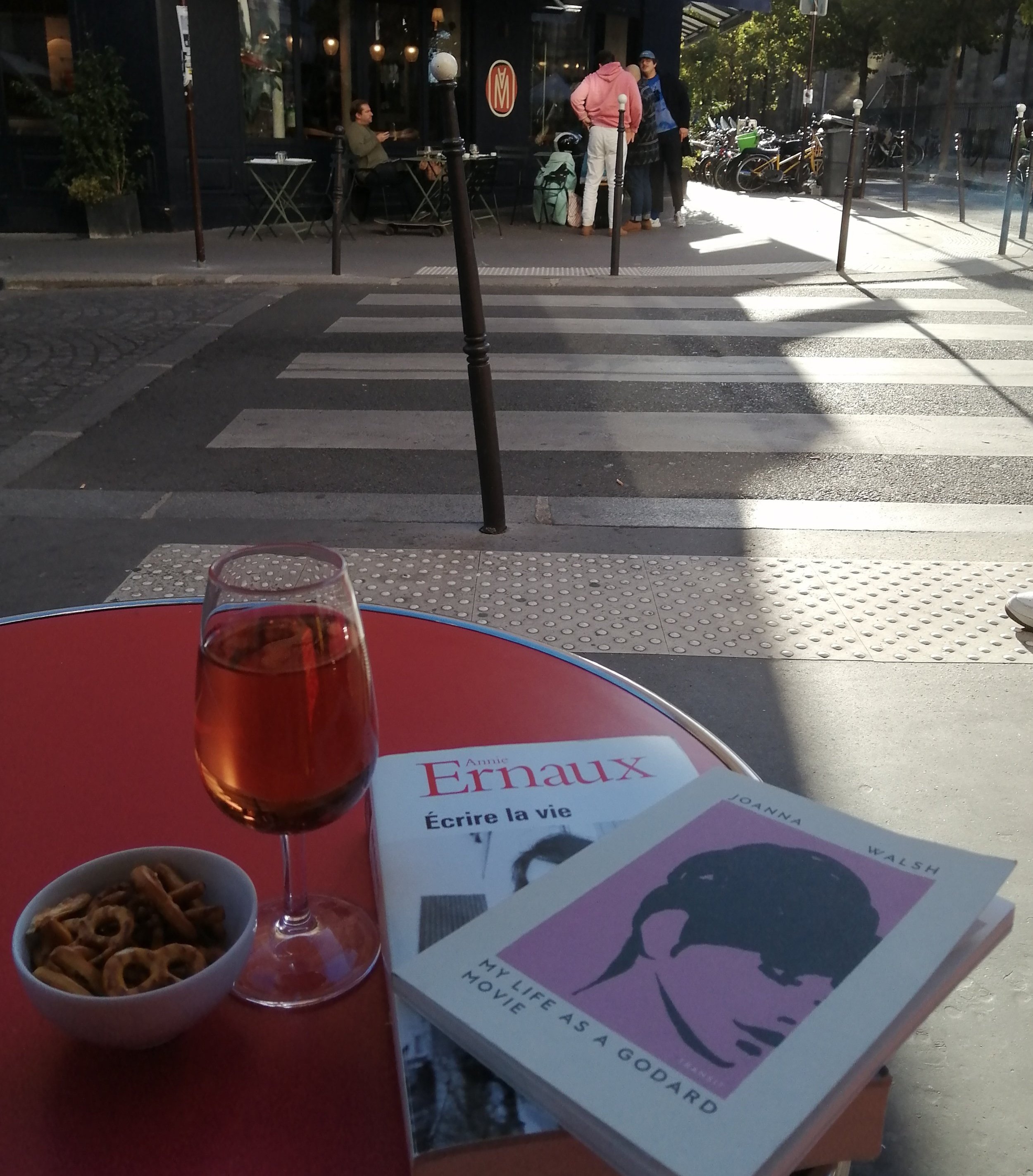

And the day after I walk round Paris because on the streets of Paris there are no deadlines which are perhaps not real things, anyway. I walk until I’m very hungry, then eat a piece of indifferent quiche from a bakery. I sit in one of my favourite cafes outside one of my favourite parks. The small, cheap coffee comes with a little round butter biscuit, a tiny carafe d’eau and miniature water glass. It’s so perfect I feel like I’m getting away with something. I stay for hours. In front of me, people walk the crossing into and out of the park, making Paris material by performing their lives. Though my performance is borrowed (for me this is never not a proxy life), I am also making something.

I write this piece.

My son, who is speaking to me again, texts me from university: have you heard of a guy called de Certeau? I might do this module…***

By coming to Paris all my life, what I have made is less an object than a trajectory; a habit, a performance, in which I am a real imposter. I have sent someone in my place. It’s me. Just as one day I will leave my life and I will come to Paris. But I will never arrive because I will always be coming here.

Notes

*Thank you to Emma Wolf Haugh, whose piece on Eileen Grey, Campaign Furniture (part of the project, Domestic Optimism), can be found here.

**Thanks to Tim Etchells, whose piece In Place of Another, was performed at la Ménagerie de verre by Terry O’Connor on 4th October 2022.

***Michel de Certeau’s The Practice of Everyday Life is a very influential text for me, and one I know well. I particularly like vol. II, Living and Cooking, in which de Certeau describes how the everyday trajectories of the inhabitants of a Paris quartier, especially women shopping for domestic goods, create a ‘neighbourhood’.

Joanna Walsh is a multidisciplinary writer, artist and arts activist. The author of eleven books including Hotel, Vertigo, Worlds from the Word's End Break.up, and Girl Online, she also writes for performance, visual art and digital narrative, often working with programming and AI. She is a UK Arts Foundation fellow, and the recipient of the Markievicz Award in the Republic of Ireland. She founded and ran #readwomen (2014-18), described by the New York Times as “a rallying cry for equal treatment for women writers” and currently runs @noentry_arts.

During her Paris residency, Joanna is running a postcard exchange project. Write her a postcard and she will respond. To learn how to participate, go here.