On a Sentence from "I Who Have Never Known Men"

I first translated Jacqueline Harpman’s 1995 novel Moi qui n’ai pas connu les hommes in 1997, and I have in fact revised this translation twice. Both revisions proved to be important stepping-stones in the development of my practice.

As I was putting the typescript in the envelope to post to the publisher at Harvill in the ’90s, I gave the translation another skim through—putting off the dreaded moment of letting it go. All along, I’d had a niggling sense that something was amiss, but I hadn’t been able to put my finger on what it was. And then it dawned on me: the narrator of this first-person fictional memoir is a woman who has a rudimentary education. She was imprisoned with thirty-nine other women in a bunker during her adolescence, and then roamed a barren landscape for years. Through it all, these women—who themselves had limited education—were her only teachers, until later in life, when she gleans knowledge from a cache of books she discovers. The French text reads with exquisite elegance, and, in translating it, I had taken my cue from its rhythms and cadences. As I was giving my work that final panic read, I realized that I had replicated the ponderous Latinate vocabulary. French derives chiefly from Latin and does not offer as many linguistic registers as English. I became acutely aware that I had unconsciously employed the Latin-root words suggested by the French, which sounded incongruous in English, given the narrator’s background and circumstances. I then went through the translation with a fine-tooth comb and substituted Anglo-Saxon-root words for as many Latinate words as I could, and replaced polysyllabic with monosyllabic terms where appropriate, which sounded so much more natural coming from this narrator.

That lightbulb moment is something that has illuminated all my subsequent work, and I think carefully about the ratio of Latinate to Anglo-Saxon-root words for every translation that I do. It is also something I incorporate into my teaching.

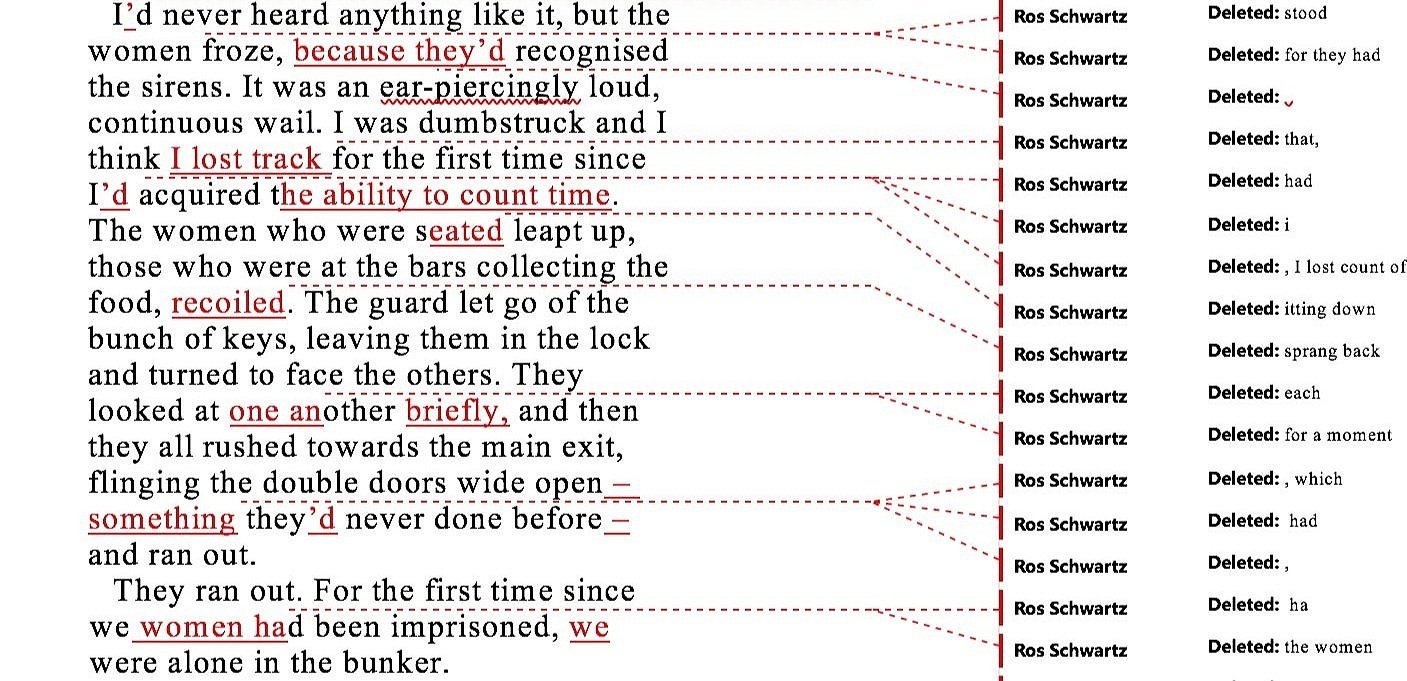

Revisiting my translation again for this edition, I focused on different infelicities. I read the text aloud and it struck me that there were countless instances where the narrator’s voice demanded a contraction, such as ‘isn’t’, ‘couldn’t’, ‘she’d’ etc., but I hadn’t used any contractions in the original translation. Had language evolved since the 1990s, or had I? I also found a number of ways to simplify and condense the language, especially in the most dramatic passages.

Translators are not often given the opportunity to reprise their own work. We say glibly that a translation is never finished, that it can always be improved, and this has been confirmed for me page after excruciating page.

Ros Schwartz has translated numerous works of fiction and non-fiction from French, including several Georges Simenon titles for Penguin Classics, a new translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince and, most recently, Mireille Gansel’s Translation as Transhumance. The recipient of a number of awards, she was made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2009 and received the Institute of Translation and Interpreting’s John Sykes Memorial Prize for Excellence in 2017.